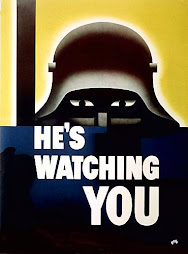

Privacy advocates plan to call on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to suspend use of "whole-body imaging," the airport security technology that critics say performs "a virtual strip search" and produces "naked" pictures of passengers, CNN has learned.

A TSA employee, shown from the back, as he stands in an airport whole-body imaging machine.

The national campaign, which will gather signatures from organizations and relevant professionals, is set to launch this week with the hope that it will go "viral," said Lillie Coney, associate director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, which plans to lead the charge.

"People need to know what's happening, with no sugar-coating and no spinning," said Coney, who is also coordinator of the Privacy Coalition, a conglomerate of 42 member organizations. She expects other groups to sign on in the push for the technology's suspension until privacy safeguards are in place.

Right now, without regulations on what the Transportation Security Administration does with this technology, she said, "We don't have the policy to hold them to what they say. They're writing their own rule book at this point."

The machines "detect both metallic and nonmetallic threat items to keep passengers safe," said Kristin Lee, spokeswoman for TSA, in a written statement. "It is proven technology, and we are highly confident in its detection capability."  Watch a video of the body-imaging scans »

Watch a video of the body-imaging scans »

Late last month, freshman Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, introduced legislation to ban these machines. Of concern to him, Coney and others is not just what TSA officials say, it's also what they see. iReport: Tell us what you think about these scanners

The sci-fi-looking whole-body imaging machine -- think "Beam me up, Scotty" -- was first introduced at an airport in Phoenix, Arizona, in November 2007. There are now 40 machines, which cost $170,000 each, being tested and used in 19 airports, said TSA's Lee.

Whole-Body Imaging

These six airports are using whole-body imaging as a primary security measure, according to TSA:

San Francisco, California

Miami, Florida

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Salt Lake City, Utah

Las Vegas, Nevada Six of these airports are testing the machines as a primary security check option, instead of metal detectors followed by a pat-down, she said. The rest present them as a voluntary secondary security option in lieu of a pat-down, which is protocol for those who've repeatedly set off the metal detector or have been randomly selected for additional screening.

So far, the testing phase has been promising, said Lee. When given the choice, "over 99 percent of passengers choose this technology over other screening options," she said.

A big advantage of the technology is the speed, said Jon Allen, another TSA spokesperson, who's based in Atlanta, Georgia. A body scan takes between 15 and 30 seconds, while a full pat-down can take from two to four minutes. And for those who cringe at the idea of being touched by a security official, or are forever assigned to a pat-down because they had hip replacements, for example, the machine is a quick and easy way to avoid that contact and hassle, he said.

Using millimeter wave technology, which the TSA says emits 10,000 times less radio frequency than a cell phone, the machine scans a traveler and a robotic image is generated that allows security personnel to detect potential threats -- and, some fear, more -- beneath a person's clothes.

TSA officials say privacy concerns are addressed in a number of ways.

The system uses a pair of security officers. The one working the machine never sees the image, which appears on a computer screen behind closed doors elsewhere; and the remotely located officer who sees the image never sees the passenger.

As further protection, a passenger's face is blurred and the image as a whole "resembles a fuzzy negative," said TSA's Lee. The officers monitoring images aren't allowed to bring cameras, cell phones or any recording device into the room, and the computers have been programmed so they have "zero storage capability" and images are "automatically deleted," she added.

But this is of little comfort to Coney, the privacy advocate with EPIC, a public interest research group in Washington. She said she's seen whole-body images captured by similar technology dating back to 2004 that were much clearer than what's represented by the airport machines.

"What they're showing you now is a dumbed-down version of what this technology is capable of doing," she said. "Having blurry images shouldn't blur the issue."

Lee of TSA emphasized that the images Coney refers to do not represent millimeter wave technology but rather "backscatter" technology, which she said TSA is not using at this time.

Coney said she and other privacy advocates want more oversight, full disclosure for air travelers, and legal language to protect passengers and keep TSA from changing policy down the road.

For example, she wants to know what's to stop TSA from using clearer images or different technology later. The computers can't store images now, but what if that changes?

"TSA will always be committed to respecting passenger privacy, regardless of whether a regulation is in place or not," Lee said.

She added that the long-term goal is not to see more of people, but rather to advance the technology so that the human image is like a stick-figure and any anomalies are auto-detected and highlighted.

But Coney knows only about what's out there now, and she worries that as the equipment gets cheaper, it will become more pervasive and harder to regulate. Already it is used in a handful of U.S. courthouses and in airports in the United Kingdom, Spain, Japan, Australia, Mexico, Thailand and the Netherlands. She wonders whether the machines will someday show up in malls.

The option of walking through a whole-body scanner or taking a pat-down shouldn't be the final answer, said Chris Calabrese, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union.

"A choice between being groped and being stripped, I don't think we should pretend those are the only choices," he said. "People shouldn't be humiliated by their government" in the name of security, nor should they trust that the images will always be kept private.

"Screeners at LAX [Los Angeles International Airport]," he speculated, "could make a fortune off naked virtual images of celebrities."

Bruce Schneier, an internationally recognized security technologist, said whole-body imaging technology "works pretty well," privacy rights aside. But he thinks the financial investment was a mistake. In a post-9/11 world, he said, he knows his position isn't "politically tenable," but he believes money would be better spent on intelligence-gathering and investigations.

"It's stupid to spend money so terrorists can change plans," he said by phone from Poland, where he was speaking at a conference. If terrorists are swayed from going through airports, they'll just target other locations, such as a hotel in Mumbai, India, he said.

"We'd be much better off going after bad guys ... and back to pre-9/11 levels of airport security," he said. "There's a huge 'cover your ass' factor in politics, but unfortunately, it doesn't make us safer."

Meantime, TSA's Lee says the whole-body imaging machines remain in the pilot phase. Given what the organization has gleaned so far, she said additional deployments are anticipated.

Posted via email from Refuse 2 Be Programmed